I recently came across an allegation on Amazon.com that got me thinking. The review in question is by Andrew Grobengieser, and it is critical of the Manhattan Transfer’s latest album, The Chick Corea Songbook. Grobengieser alleges:

As a lifetime fan, I was unbelievably excited to hear of the release of a Chick Corea songbook. And then I listened. It only took me a moment before a sinking feeling set in, as I realized that ManTran, one of the best-blending and most in-tune vocal ensembles in recorded-music history, has succumbed to the scourge of modern recording known as “Auto-Tune”. Yes, Manhattan Transfer fans, welcome to the world of GLEE and Cher. It’s all over the place on group harmonies, and even rears its ugly head on a few of the solo vocals.

I mean, really. Why ON EARTH would this production choice be made? It takes what are otherwise very hip and adventuresome arrangements, and makes them roboticized, metallic, cold and inhuman.

It seems to me that it’s one thing to allege that a weekly TV musical is using Auto-Tune but quite another to level the accusation at four vocal jazz icons.

I am by no means anything approaching an expert on this topic — just an interested fan. But the engineer in me was curious: Is it actually possible to detect the use of Auto-Tune?

First, I did a little background research. Auto-Tune is a tool that can be used to correct the pitch of recorded singing. Evidently it can be used in a subtle or blatant manner; Andy Hildebrand, the inventor of Auto-Tune, says:

At one extreme, Auto-Tune can be used very gently to nudge a note more accurately into tune. In these applications, it is impossible for skilled producers, musicians, or algorithms to determine that Auto-Tune has been used. On the other hand, when used as an effect, such as in hip-hop, Auto-Tune usage is obvious to all. Everything in between is subject to an individual’s unique listening skills.

This raises the question: Assuming that the Manhattan Transfer is attempting to use Auto-Tune in a subtle manner, how can Grobengieser detect its use? (In a follow-up comment to his review, he claims he is “a trained musician, with years of experience dealing with vocal group intonation.”) Frankly, I didn’t believe he could detect it, so I decided to try to learn more.

According to one site:

The most important parameter is the retune speed — the time it takes Auto-Tune to glide the note to its perfect pitch. For maximum realism, the retune speed must be set to a value close to the retune speed of the singer’s natural voice. . . . But Auto-Tune’s retune speed can be set to any value right down to zero, which means that notes instantly jump to the exact pitch. This effect is decidedly unnatural. If the singer glides smoothly from one note to another, Auto-Tune will suddenly jump from one note to the next when the mid-point between them is reached.

I believe you can hear the unnatural Auto-Tune effect with a zero retune speed in this Cher song, which according to various web sources also seems to be the first use of Auto-Tune as a sound effect (in 1998).

But let’s assume that the Manhattan Transfer is trying to hide the use of Auto-Tune, in which case their recording engineer would presumably use a retune speed that approximates a “natural” value.

Hildebrand’s original patent for Auto-Tune, also from 1998, has a relatively clear explanation of his invention and how it works. (In my experience, the technical clarity is unusual for a patent!) If you’re interested, I recommend the discussion from the middle of column 3 to the middle of column 6.

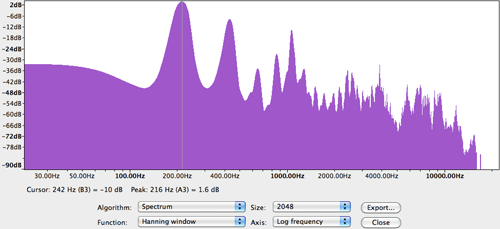

I wondered if possibly we could detect Auto-Tune because the notes would be too perfect. The song “500 Miles High” begins with an a capella intro in which it is easy to isolate the first note sung by Janis Siegel. I brought this song into Audacity and zoomed in to the first one second of the left channel, and then selected Analyze > Plot Spectrum.

This is a reasonably crude method, but if you can use it at a point in the music where you can isolate a single voice, it can show some interesting information. Above, if I’m remembering my music theory class correctly, you can see that Siegel is singing an “A.” You can see the fundamental in the first peak, which is highlighted with the thin vertical line in the screenshot above. To the right are all the harmonics.

As you can see, the plot shows that Siegel didn’t hit a perfect “A” — that would have been at 220 Hz. Instead, she’s at 216 Hz, which would be noticeably flat. I am definitely no expert, but I’m thinking that if you’re going to use Auto-Tune, why not get the note correct?

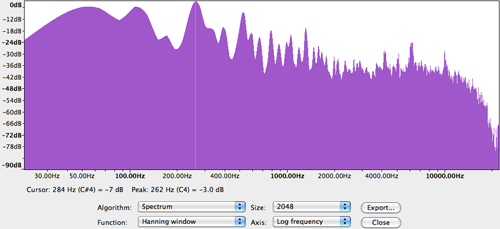

There is a similar intro to the Manhattan Transfer song “Gentleman With a Family” from 1991’s The Offbeat of Avenues. I picked this song because it starts out similarly to “500 Miles,” and also because 1991 puts it well before Auto-Tune would have been in use. In this case, the intro isn’t a capella, so there is some instrumentation playing and thus it’s a little harder to isolate just the singer’s voice. However, selecting the left channel from 20.5 to 21.5 seconds in this song yields the following frequency analysis:

I am pretty certain that the highlight is again on the fundamental of Siegel’s voice — she is hitting a C at 262 Hz. (I believe the peaks to the left are lower tones from the instruments.) Here, before the days of Auto-Tune, she’s dead-on. Of course, she was also 19 years younger!

There are many more sophisticated methods of analysis that suggest themselves. It would be interesting to plot the frequencies over time — perhaps a voice held on a long note without any variation would be a likely indicator of the use of Auto-Tune. If we could isolate each singer onto a separate voice track, it would even be possible to run the pitch detection portion of the Auto-Tune algorithm; if this indicated that tuning was necessary, it would probably be a good clue that Auto-Tune wasn’t used in the studio. My colleague Kevin Gross suggested looking at the vibrato and timbre because vibrato is removed altogether by Auto-Tune (and then artificial vibrato is usually added back in, according to the patent), and timbre would be changed when samples are added or dropped as part of the tuning process.

Obviously, I can’t really conclude anything from what I’ve done so far. In his Amazon review, Grobengieser doesn’t specify where he thinks he hears Auto-Tune on The Chick Corea Songbook; possibly he’s not talking about the intro to “500 Miles.” Or possibly my analysis tools are not sophisticated enough to detect the use of Auto-Tune. Or possibly if you are an audio engineer trying to sneak a little Auto-Tune into a jazz recording, you are smart enough not to correct to the exact pitch. I have no idea. To my ears, the transfer occasionally sounds just a little off-key on this album, which I ascribe to their age (but it also argues against the use of Auto-Tune). Again, though, I’m no expert.

I’d welcome your thoughts in the comments!

Howdy Pierce is a managing partner of Cardinal Peak, with a technical background in multimedia systems, software engineering and operating systems.